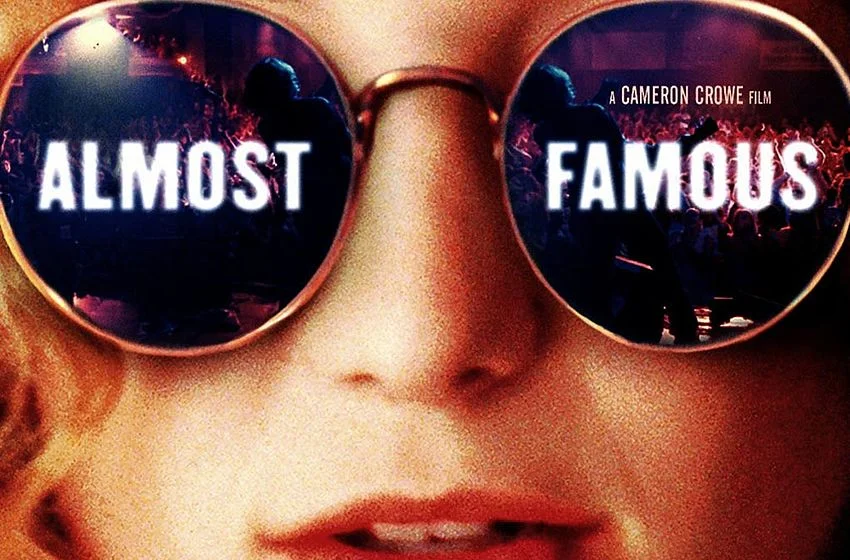

5. Almost Famous (2000)

In the name of journalistic transparency, I must admit that Almost Famous has held the top spot on my list of favorite movies since I first watched it at a janky Pasadena theater in 2000. I was the same age as William and possibly Penny (though she’s tougher to pin down) and, while we occupied different worlds during different times, their comings of age are forever linked with mine. Be it through nostalgia or sheer perfection, the film hasn’t wavered from that top spot in nearly twenty years. I come back to it often - like one returning to a favorite album - for comfort (“You are home”), for inspiration (“I used to do speed, you know, and sometimes a little cough syrup....just to fucking write”), to laugh (“How can you tell? I’m just one of the out of focus guys”) and to cry (“What kind of beer?”). And each time, I revert to my nascent state of fandom, rather than maintain a critical eye. This latest watch was of the tightly-paced theatrical release, though I’d be remiss if I didn’t also recommend the considerably longer director’s cut - a bootleg version ironically called Untitled - as it features one of the all-time steamiest love scenes set against the chilly backdrop of a Continental Hyatt House ice machine.

What do I love about Almost Famous? To begin with, everything. Writer/Director Cameron Crowe and company have shown me what it’s like to love some silly little movie so much it hurts. There’s Penny Lane and her pack of eccentric band-aides; there’s the way fictional Stillwater pulls off a convincing portrayal of a 1970s rock band, jealous and fighting and breaking up; there’s the way the musical setpieces convey both the excitement of performing live before a screaming crowd as well as the intimacy of listening to an album alone in your room; there’s the soundtrack of greatest hits and deep cuts, most notably the healing effect of Elton John riffs when personal rifts run deep; there’s Lester’s cynicism, Penny’s optimism and William’s idealism creating perfect harmony. “I’d keep going but my glass is full.”

Early in the film, famous rock journalist Lester Bangs waxes poetically during a radio interview that which essentially becomes the movie’s thesis: “Here’s a theory for you to disregard completely. Music, you know, true music, not just rock and roll, it chooses you. It lives in your car, or alone, listening to your headphones, you know, with the vast, scenic bridges and angelic choirs in your brain. It is a place apart from the vast, benign lap of America.” Music’s innate power comes from its ability to connect no matter the individuality of experiences. And, within the context of Almost Famous, that “place apart” is the one bringing Russell and Penny and William, Jeff and Polexia and Sapphire together, and it seems to exist in direct conflict with the real world they desperately try to avoid. In the real world, high school senior and aspiring journalist William Miller has tests in need of taking and a garbage disposal in need of fixing. Back in the real world, Penny Lane’s mom has only one aspiration for her daughter and that is to marry well. The bandmates have wives and girlfriends, big houses and bigger responsibilities. Home is work and so the road becomes home.

To maintain the facade - this dichotomy between the real world and the place apart - infamous “band-aide” (“Groupies sleep with rockstars because they want to be near someone famous...we’re here because of the music”) Penny Lane lives according to intellectually sound, though emotionally flawed, logic: “I always tell the girls to never take it seriously. If you never take it seriously, you never get hurt. If you never get hurt, you always have fun. And if you ever get lonely, you just go to the record store and visit your friends.” She insulates herself from reality by creating a false one complete with “all these rules and all these sayings and nicknames.” She has assumed a pseudonym and is preceded only by her reputation (“I’ve done twice the things I said I’ve done”). William forges a fake (read: older, more experienced) identity in his communications with Rolling Stone. Everyone deploys clever aliases at various hotels. They are all playing their part in this interlude, and secrets are the currency doled out to foster a false sense of intimacy and camaraderie, "You made friends with them. See, friendship is the booze they feed you. They want you to get drunk on feeling like you belong."

While tumultuous relationships and looming deadlines provide much of the film’s dramatic tension, the greatest conflict is found in the push and pull between appearing cool and being authentic. During their first meeting, backstage at a Stillwater show, Penny furrows William’s brow and tells him, “Now you’re mysterious,” which she intends as the greatest of compliments. For all the ways avoidance of the real world is imperative, giving away too much of yourself is likewise. Penny collects strays wherever she goes, and then feigns ignorance as William introduces her to Russell Hammond, Stillwater’s sexy lead guitarist (loosely based on Gregg Allman of the Allman Brothers), “Have we met?” Later, when Russell initiates contact to make amends with Penny, he maintains the pretense of being endlessly important, “I can’t really talk right now, I’m in a room full of people,” before getting real, “Actually, I’m alone.” In the context of discussing the content of the piece with William, he has one small off the record request: “Just make us look cool.” Their personas are carefully cultivated to the point of becoming burdensome reputations to uphold, “Is it that hard to make us look cool?” Russell, having surpassed his band mates as musicians and thinkers, understands this innately, “Maybe we don’t see ourselves the way we really are.” About midway through the film, the band gets in an argument over new merchandise. The tee shirt has a prominently featured Russell with the rest of the bandmates dark and blurry behind him. Lead singer Jeff Beebe is understandably upset, prompting Russell to retort, “You love this shirt - it let’s you say everything you want to say.” After the blow up, everyone angrily scatters with Russell pledging, “From here on out, I’m only interested in what is real. Real people. Real feelings.” William swipes the souvenir before joining Russell in his quest. Such realness is finally achieved late in the film when a near-death experience compels the men to finally admit the truth in a series of escalating confessions. And in a cruel twist of fate, they pull through the turbulence and must now live with consequences of being honest and unmerciful.

For a movie with no shortage of theories about artistic musical harmony, Almost Famous is not lacking in ideological dissonance. William’s internal struggle reflects a greater tension within cultural consumerism - that of being a fan and also maintaining critical distance. As a period piece of sorts, the movie provides an interesting window into the old world of celebrity profiles and journalistic access. It didn’t bother me then, though it’s deeply sinister now that the members of Stillwater refer to William (aka a rock writer) as “The Enemy.” And yet, he’s brought onto their tour bus and into their world: “Hey William, we showed you America. Did everything but get you laid.” Even Penny initiates him, “You’re one of us.” William is decidedly absent from the movie’s promotional poster, which features a close-up of Penny’s face with Russell and the cheering crowd reflected in her round, rose-colored sunglasses. She takes an optimistic view of the world as a means of always having fun. The place apart is not without conflict, but there is no true enemy. There are no bad guys and no villains. Everyone is simply struggling and coming to terms with their own limitations.

Before she “retired,” at the troubling age of sixteen, Penny made her own, less marketable, contribution to the world of rock and roll. She started a school for band-aides and said, “No more exploiting our bodies and our hearts. Just blow jobs.” She sees herself as a muse, someone who inspires the music by helping talented artists reach their full potential. Penny believes she’s in control. She’s the one taking advantage of Russell and the situation. She wields her beauty and sexuality as agents of power, and relies on William as an ally and co-conspirator. He’s provides cover, “her reason for coming,” and a safety net when her relationship with Russell is too tempestuous. But for all her mysterious looks and hanging questions, Penny’s motives are transparently simple, “He’s my last project and I think we should do it together. Because all the guys are good but he could be great.”

Crowe’s characters are well-drawn and well loved, and he imparts superficial archetypes - the guitarist with mystique, the frontman, the mysterious muse, the groupie, the obsessive fan, the rock writer - with real (there’s that word again) depth and interiority. He makes you fall in love with them just as William does and, presumably, just as he did. Or maybe that’s just me. Because if these characters are archetypes, then I’m undoubtedly a William - impressionable, more comfortable outside the inner circle, observing, taking notes with my eyes. Even when I thought I was cool, I knew I wasn’t.

Whether he is your spiritual surrogate or not, William is meant to play the role of audience stand-in. He is our entrée into this world. His perspective and point of view are ours. We don’t know what happened last summer between Penny and Russell. We don’t what he says to her in private. Questions are evaded; interviews are put off; doors, duct taped with “Do Not Disturb” signs, are slammed in our faces. And yet, we come to learn Penny’s fate before she does. The scene in which William explains what happened in that boys’ club backroom poker hand - hurt and angry on her behalf - never fails to break my heart. Penny believes she and Russell are in love “as much as it can be for someone...” when William cuts her off with unmerciful honesty, “Who sold you to Humble Pie for fifty bucks and a case of beer? I was there!” She stares at him, first in disbelief and then fully understanding what he’s been trying not to say this entire conversation. When she turns away, wounded, he quietly apologizes. Turning back, eyes red and watery, a tear falls down her cheek. Looking on, she brushes off the admission and away the tear, before smiling and asking, “What kind of beer?” She failed to heed her own advice. She took it seriously and can’t let anyone (except William) know how much it hurts. Perhaps they’re both too sweet for rock and roll.

I did not have this cinematic reference point until years later, but Almost Famous, while semi-autobiographical in setting and scope, is more precisely a retelling of Billy Wilder’s The Apartment, which Crowe has credited as his favorite film. I personally love the fact that Crowe sampled Wilder’s work in his own, just as a smooth baseline or simple piano melody can be reworked to send up a classic and create something new. It speaks beautifully to the power of art to inform and inspire, and gives insight into how Crowe has navigated the lines between being a fan, critic, and creator.

It’s no surprise Almost Famous plays like an understated jukebox musical of 1970s greatest hits, with each cue perfectly capturing the emotional tenor of each scene. No doubt because of my age, the movie soundtrack was my first introduction to several of these classics and I’m not able to separate The Wind from the image of Penny spinning around an empty auditorium. According to his sister’s advice, William listens to The Who’s Tommy and burns a candle with the promise of seeing his future. This track befittingly scores the transition as William ages from eleven(!) to fifteen. We often think of music as having transportative properties tending towards traveling back to a particular place and time in the past. Nothing elicits the same emotional recall as music, though I love the idea that it somehow also informs the future.

The year is 1973 and Lester Bangs has another theory: It’s just a shame you missed out on rock and roll...It’s over. Everyone seems to knows it’s true, though they are not ready to leave this place apart for the real world just yet. William’s graduation and deadline loom large. Penny is retired. The band is on the rocks. Polexia went to England with Deep Purple. All of these beloved characters claim to be no good at goodbyes. They hate the finality. They reject the implication that something is over and it’s time to move on. In fact, they never utter the word unless disparaging it, opting instead for nods and waves and last looks. And when Russell finally calls Penny to make things right, he implores her to “say all the things we never said.” Though she, wise beyond her years and in need of a new crowd, knows the only thing left unsaid is “goodbye.” In the final frames, William gets his key interview and affectionate family reunion; Penny cashes in her partial tickets for a window seat to Morocco; Stillwater goes back to their bus and back on tour; and stories that appear to end are just beginning anew.