Cuba | August 2016

IN FLIGHT

Travel time: 12 hours, 40 minutes (LAX to MEX to HAV, palindromically)

Miles covered: 5,300 (roundtrip)

Movies consumed: 2.5 (Hail, Caesar; Hello, My Name is Doris; first half of Everybody Wants Some!!)

Hours slept: approximately four

POST FLIGHT

Travel time: 11 days

Miles covered: 613 (via car and bus and bicycle)

Pulled pork sandwiches consumed: no less than five

Currency: As the millennials says, it’s complicated. CUC is the Cuban convertible peso used primarily by tourists. It is valued one-to-one against the US Dollar, however, the exchange is heavily taxed (more so than other foreign currencies) so 1 CUC = $.87 USD. CUP is the Cuban peso used primarily by Cubans at neighborhood food stalls, cafeterias and markets, approximately 25 CUP to 1 CUC. It is perfectly legal for travelers to use either form of currency. We exchanged a small amount of CUC into CUP in order to sample the less expensive street food scene. If possible, bring Euros or Canadian Dollars to exchange for CUC in Cuba. Both Mexican pesos and USD have unfavorable exchange rates. I would advise studying the two currencies beforehand. There are some street scams specifically designed to take advantage of flummoxed travelers.

[Note: take extra cash with you, more than you think you need. We did not have access to ATMs or credit cards while abroad.]

Prologue:

There were (and still are) many gaps in my understanding of Cuban history. I tried to cram in advance of my trip and, at the very least, keep my mind and ears open during our visit. Here are the Cliff’s Notes. Cuba was a Spanish colony and prosperous trading partner of the U.S. After some rebel successes in Cuba’s second war of independence in 1897, U.S. President William McKinley offered to buy Cuba for $300 million. Rejection of the offer compounded by an explosion sinking the American battleship USS Maine in Havana harbor led to the Spanish–American War. Exactly who is responsible for sinking this naval ship remains a point of contention. Conspiracy theories and questions of guilt aside, the Spanish were blamed. The inflammatory incident gave the United States just the ammunition it needed to engage in a battle for Guam, Puerto Rico and, most importantly, Cuba. The United States only agreed to withdraw its troops from Cuba when Cuba agreed to the provisions of the 1901 Platt Amendment allowing the U.S. to intervene in Cuban affairs if necessary to maintain good government and committed Cuba to lease land to the U.S. for naval bases, i.e. Guantanamo Bay. The rise of General Fulgencio Batista in the 1930s to de facto leader and two-term President of Cuba led to an era of close cooperation between the governments of Cuba and the United States. The Batista era witnessed the almost complete domination of Cuba’s economy by the United States, though corruption was rife and Havana became a popular sanctuary for American organized crime figures, i.e. Meyer Lansky.

In 1959, Fidel Castro, Che Guevara and Castro’s younger brother, Raul, led the uprising against Batista’s government. Fidel was an enigmatic lawyer with his sights on overthrowing this right-wing government in order to assume political and military power for himself. Che was the socialist revolutionary. As a young medical student, he was radicalized by the poverty, hunger and disease he witnessed. His desire to overturn what he saw surely led to his partnering with the Castro brothers. Killed at the age of 39, Che lives on as a counterculture symbol of rebellion and a champion of leftist movements in the way that only a young martyr can. Castro survived and governed long enough to solidify his standing as a polarizing world figure. His supporters view him as a champion of socialism and anti-imperialism whose revolutionary regime advanced economic and social justice while securing Cuba’s independence from American imperialism. Critics view him as a dictator whose administration oversaw human-rights abuses, the exodus of a large number of Cubans, and the impoverishment of the country’s economy. I must admit I was more critic than supporter and was caught off guard observing firsthand just how beloved he was in Cuba. I guess both our countries are propagated with propaganda.

The U.S. opposed Castro’s government and unsuccessfully attempted to remove him from power by assassination, economic blockade and counter-revolutions. To combat these threats, Cuba formed an alliance with the Soviet Union, allowing the Soviets to place nuclear arms there, just 90 miles off the coast of Florida. This is the Cuban Missile Crisis. President Kennedy avoided nuclear war, but tensions between U.S. and Soviets (capitalism vs. communism) continued to escalate. The trade embargo was tightened under President Reagan. However, Cuba’s economy was stable until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, both of which collapsed in 1991. Widespread poverty followed.

In 2006, citing his ailing health, Fidel stepped down and handed the reins of power to the less radical Raul. Raul instituted more progressive policies, allowing Cuban citizens to own and run private businesses, casa particulares (basically Airbnbs) and paladares (restaurants operated out of Cubans’ domestic kitchens). He worked with President Obama to reopen lines of communication and lift the international travel ban that had prohibited U.S. citizens from entering Cuba for over 60 years. Prior to the election of Donald Trump in 2016, it was assumed the trade embargo would be the next Soviet-era policy to fall. Despite the influx of eager tourists and cruise ships, most Cubans still lack basic goods such as toilet paper and soap. Rescinding the embargo would go a long way toward allowing access to valuable resources. They are desperate for pens and paper and gossip magazines – any “news” from the world beyond their borders, any content that is not regulated and produced by their government.

The gas stations run out of gas. Infrastructure is crumbling. Expanding potholes cause frequent flat tires. The supermarkets – with bare torn apart shelves save for bottles of Havana Club rum and vegetable oil – are more indicative of an oncoming zombie apocalypse than booming Bahamian island. And yet, they make do: with old American cars and less old Japanese steering wheels and gear shifts; with metal chairs repurposed as BBQ grills; with unneeded dryer motors powering lawnmowers; with over-salted food and over-sweetened cola. They are an island of life hackers and do-it-yourself engineers. Out of necessity, they mothered invention.

Chapter Uno:

I guess now that I have successfully reentered the country, I should make no secret of the fact that (technically) I travelled to Cuba “illegally.” We were able to book all accommodations online without confirming any connection with the People to People humanitarian program. In August 2016, commercial airlines were not offering direct flights between the U.S. and Cuba. Unless you had the means to charter a jet (we didn’t), people were traveling through Mexico (as we did). We circumvented the “People to People” program by purchasing round trip fares from Mexico City to Havana, Cuba via Mexican airline, Interjet. At the ticket counter, prior to checking in, we purchased Cuban travel visas for $25. This was the document (separate from our passports) that would be stamped as we entered and exited Cuba. Within two hours, we are transported to the largest island in the Caribbean and, in many ways, back in time. We clear customs and are greeted by Luis, the gentleman who will be driving us to our particular casa particular. Before leaving the airport, we exchange money. There are two casa de cambios located on the curb just outside the arrivals area. Hustle out there if you can because the lines are long and the tellers slow, assisting just one customer at a time.

We are scheduled to spend our first three days in the capital city of Havana. Luis drives us from the airport to the city in his rusty black 1946 Chevy. The pre-arranged fare is 25 CUC. Luis points out Revolution Square where the faces of Guevara and Castro grace the buildings’ facades. The installations are quite spectacularly lit up at night. Suddenly, the car slows, Luis pulls over and puts his head in his hands, “Que disastre! That is Cuba.” We exchange furtive glances, unsure of just how dire the situation is. As it turns out, we just ran out of fuel. The indicators in his 70 year-old Chevy (a symbol of great American industry as much as the Cuban people’s resourcefulness – cobbling together American chassis with gear shifts and steering wheels from Japanese imports) no longer serve their function, keeping his mileage and speed and fuel levels a constant guessing game. Luis fills the tank from a gas can in his trunk. Luckily, he had reserves with him since later in the trip, we came to learn that fuel – like most necessities in Cuba – is hard to come by and fueling stations often run out during the day. With our first crisis averted, we proceed to La Colonial 1861 in the lush neighborhood of Vedado. The room is adequate with two bedrooms on two levels, life-affirming air conditioning, and a large bathroom. The one and only time we glimpse Armando, who was praised on TripAdvisor for his hospitality, is upon arrival. Cuban homeowners have been capitalizing on the Airbnb business model since 2006, when Raul Castro took the reins and essentially legalized these privately owned and operated bed and breakfasts. The casa particulars, in addition to offering cheaper accommodations than hotels, also present a much more authentic experience.

That afternoon we walk along the Malecon, Havana’s 8km-long seawall and boardwalk. One of our hosts told us that the Italian Mafia built the Malecon with the intention of populating it with resort hotels and casinos. The financing eventually fell through, but the iconic esplanade remains. We pass men selling bags of bugle-shaped snacks, others casting for fish beyond the break, boys playing pickup baseball, amateur boxing matches, young couples sharing earbuds while basking in the sun’s final minutes.

For some reason, the busy six-lane highway is closed to cars this evening. We walk right down the middle of this empty thoroughfare. As we approach the swanky Hotel Nacional, we are met with the sights of salsa dancing and smells of fried meats. Tonight marks the kickoff of the annual salsa dancing festival, complete with carnival food, amateur dance competitions and float-filled parade. Feeling adventurous ourselves, we nosh on unidentifiable street meat and beer. The stalls’ offerings are priced in CUP, which we do not have yet, so we pay in CUC. The vendors happily accept and provide some change, applying their own favorable rate to the exchange. The Cubans are very friendly and sociable. A friend warned that 90% of the locals are eager to talk to you, and then 90% of those want money. We had nothing but positive encounters, however, you cannot help feeling you are being consistently scammed in small ways.

We continue walking to La Habana Vieja (Old Havana). Old does not even begin to describe it. La Habana Vieja is quite literally falling apart. Buildings in varying degrees of decay are occupied by brave squatters. Horse-drawn carts navigate the torn up streets alongside bicyclists, pedicabs and old American cars. Patriotic graffiti’ed murals honoring Che and the Revolution adorn the crumbling facades of buildings, evoking the faded glory and eroded optimism of Spanish Colonialism followed by independence. Children play futbol and baseball in the streets. All the boys have the same haircut – cropped close on the sides and left long on top. The sole barbershop has a never-ending queue. Even a casual observer can see how difficult their lives are; how they make do with so little; how the $3 I spent on a cocktail is half their weekly wages. And here I am: wandering these streets, inspired by the reflected magic hour light, excited by each interaction, marveling at the country’s beauty and the sheer resourcefulness of its denizens. I am having a wonderful time and plagued with guilt because of it.

Lately, the concept of living in a bubble of your own making – be it socio-economic, racial, educational or all of the above – has been written about and discussed ad nauseam. But perhaps nowhere is this phenomenon more keenly observed than Cuba. Living on an island can be incredibly isolating, literally and figuratively. Living on an island under a Communist dictatorship is downright fascist. The Cuban people have been living in their particular bubble for over 50 years. It is not hard to imagine the ways in which a people and culture might endure the effects of this isolation from the rest of the world. It is not difficult to understand the correlation between the exchange of ideas and forward progress. Due in no small part to their confinement (and in spite of it), they have cultivated a unique way of life, in which relics of a bygone era are painstakingly preserved, often melded and modernized to create something new. Cuba and its people have been starved for these outside experiences and influences. No strangers to making do without, there exists a vibrancy to their culture, a curiosity to the people, a desire to connect. In many places, the country still looks war-torn, but there is something more interesting and important happening under the surface. A new revolution is being fought. Their war is no longer one waged with propaganda and guns and infidels, but with knowledge and information and commerce. There is a palpable sense that change is coming, a cruise ship spotted on the horizon line. After decades spent under a regime that prohibited the free-flowing exchange of ideas and discourse regarding religion, politics, arts and culture, cuisine, the walls built to keep Cubans in and others out are finally breaking down. The bubble is bursting.

Our first stop in the old town is Frente on O’Reilly Street. This unremarkable storefront actually leads to a bustling restaurant and rooftop bar. Despite a packed house, we manage to squeeze in for ice-cold passion fruit mojitos – just about the only thing capable of cooling us down in the summer heat. Pre-Cuba, the best piece of travel advice I received was “follow the music.” This first night, we do just that, letting live music lure us down the cobblestone streets of Old Havana.

In Cuba, there are several transportation options at various price points. Public buses are the cheapest but we did not dare attempt to learn the routes and fares. Taxis are the most reliable and expensive. The middle of the road option is the network of “collectivos” (or shared taxis) that, similar to buses, run along certain pre-determined routes. In theory, passengers flag down collectivos at designated pickup locations, confirm their destination/drop off point with the driver, and get a ride for about 10 CUP per person. In practice, this is easier said than done. Our first night, we loitered at one of these such pickup points (corner of Paseo de Marti and Neptuno) for at least 30 minutes. Cars would pull up, everyone would push and shove to speak with the driver, then pile into front and back seats after making some unknown negotiation. There is no line, no order; the collectivos are unmarked other than usually being less well-preserved American cars. It is chaos. Meanwhile, taxi drivers are more than willing to oblige for an exponentially higher rate. In the end, we semi-successfully negotiated a collectivo back to Vedado. But, in my opinion, saving the equivalent of $4 was hardly worth it.

Chapter Dos:

Cuba operates on island time to the extreme. Every task is difficult and time-consuming. Luckily, we are on vacation and nothing short on time. This morning’s mission includes finding breakfast and exchanging CUC into CUP. After one failed attempt yesterday afternoon (the cadeca was closed by the time we arrived), we manage to track down an open cadeca in another part of town. The operation is drastically different from last night’s collectivo experiment, but no less absurd. The exchange counter is located near the entrance of a big, open-air marketplace. There is an orderly line down the block monitored by a security guard. She ensures that only one person at a time approaches the window. Exclaim “Ultimo!” to find the last person in line. Now remember that face, since you will follow them through the line and take their place (briefly) as the new ultimo. At one point, a huge pickup truck needs to unload goods at the market. The driveway is not wide enough to accommodate both the truck and the exchange counter, so the cadeca must close up shop for 10 minutes while fresh eggs are unloaded from the vehicle. Everyone is just hanging around, chatting, shopping. Finally, we get our money, spend some on underwhelming jamon y queso sandwiches at a stand across the street, and wander the stalls selling freshly picked produce and freshly butchered meats.

I apologize for burdening you with so much extraneous information, especially since we are only on day two, but this is one of my favorite stories. During a visit to New York in 1959, Fidel Castro tasted and unsurprisingly fell in love with ice cream. After sampling each and every Howard Johnson’s flavor, Castro decided that Cuba needed to respond on a revolutionary scale by creating something bigger and better than anything his American rivals could muster, yet priced low enough for everyone to enjoy: ice cream, socialized. And so Coppelia was born. The ice cream parlor has several locations throughout Cuba, but the main park is located in Vedado. For those of you interested in trying Cuba’s premier ice cream, Coppelia is the place. But there are a few things you should know. Make sure you have CUP since scoops are the equivalent of just four cents each. The available flavors are posted on a board out front and often run out while waiting in line. Most people order the ensalada – a plate of 5 scoops – costing just 5 CUP (about $.20). And most people order more than one! As for the line, there are two and they are long. Coppelia is more about the experience than anything else. We observe teens hanging out and snapping selfies. There are entire families – from grandmothers to children in strollers – gathered in the circular dining rooms that open off the central circular staircase like, well, scoops of ice cream. The entire surface area of their tables are covered with plates of quickly melting ice cream topped with stale wafer cookies. The most opportunistic patrons bring huge tupperware for their leftovers: the Coppelian doggy bag. The structure looks reminiscent of a food court in Disneyland’s Tomorrowland – the utopic “future” as imagined by architects in the 1960s – or perhaps a cathedral with the dining vestibules separated by stained glass window panes. The three of us share three ensaladas in chocolate, caramel and strawberry, an embarrassingly small amount of ice cream compared to adjacent tables. The ice cream is better than expected but still a little sick-making. We lick our plates clean so as to not stand out any more than we already do. Coppelia has endeared itself in the hearts and tastebuds of Cubans, and now the three of us. It has also made its mark on the Cuban movie scene, serving as inspiration for the 1993 film Fresa y Chocolate. In the film, the country’s greatest cinematic success, the two male protagonists – one of whom is openly gay (another notable distinction in Cuban cinema) – meet at Coppelia. In a time of state-sanctioned persecution of gay people, Coppelia became a kind of cruising ground where strawberry and chocolate were euphemisms for sexual preference.

The eating tour continues with Cuban sandwiches in the old city and pastries at Cafe Santo Domingo (tres leche cake!). The latter features yet another long line. The shortage of basic necessities that has attended Cuban communism has made them experts at queuing. We successfully arrange a collectivo home (10 CUP each).

For dinner, we stumble upon a cheap cafeteria at the corner of Linea and Ocho. The cafeterias are named after their cross streets! We order cheap personal pizzas, then explore the tree-lined streets and verdant parks of Vedado. Lennon Parque (not to be confused with the similarly named Lenin Parque) features a sculpture of John relaxing on a bench, a quote from “Imagine” engraved at his feet. During the 1960s and 70s, when The Beatles and John Lennon were banned, dreamers and nonconformists would gather here and covertly listen to the fab four’s greatest hits. There is a Beatles-themed nightclub (Amarillo Submarine, of course!) across the street. We cannot stay long for tonight we are headed to La Fabrica, and disembark early, determined to beat the rush.

I first learned of La Fabrica del Arte Cubano through Anthony Bourdain’s Cuba-centric episode of Parts Unknown. A massive former cooking oil factory has been converted into a maze of art galleries, performance spaces, screening rooms, low-lit outdoors patios and intimate bars bringing together artists and admirers looking for inspiration, as well as clubgoers looking for a good time. FAC is open from 8:00 p.m. to 3 a.m., and this being Cuba, there is always a queue waiting to get in. We pay a cover charge of 2 CUC. At check in, we are provided ingenious drink cards, which the bartenders will mark during each order (about 3 CUC each). No money exchanges hands during the transaction and you settle your tab on the way out. A lost card demands the ultimate penalty of $25 CUC. There are multiple bars throughout the galleries and clubs. Just next door, in the old factory’s smokestack, The Cocinero offers a food menu and great open air lounge. We tour the galleries featuring a wide variety of photography and art installations (some of the artists and subjects are present to promote/discuss their works), then are charmed by a video projection of Adele performing at Glastonbury. From “Rolling in the Deep” to “Make You Feel My Love,” crowds begin to gather in the main theater area. The stools, arranged in neat rows around what appears to be catwalk that escaped our notice earlier, begin to fill. A casual glance at the schedule of events informs us that we are right on time for tonight’s main event – a live fashion show. After our introduction to fashion week, we cut out early – too tired and jet lagged and old to spend all night dirty dancing away the Havana night. Outside, the warm breeze blows the songs and sounds of Club 1830 through the salty air. We strut home making the scenic Malecon our runway.

Chapter Tres:

With a good sense of the city, we head to the beach. There is tour bus company that operates several trips daily between Old Havana and Playa Santa Maria. Round trip fare is 5 CUC per person. You can pay once seated, and will be provided a ticket for your return trip. You do not need to purchase tickets in advance. The bus picks up across the street from the Iberostar Parque Central Hotel. It being Sunday and the last day of summer vacation, we take the first departure at 9:00 a.m. The bus stops at a couple different locations. We ride to the last stop before the bus turns around. The beach is already packed with people, bringing in coolers with beer and snacks, setting up huge umbrellas and shady encampments to protect themselves from the strong Cuban sun. The beach is beautiful – white sand and clear turquoise water as far as my four eyes can see. There are stands that rent catamarans and pedal boats. Men selling hats and grapes and tamales (1 CUC each; seller unwraps the steaming tamales for us, cuts into bite-sized pieces and adds a little homemade hot sauce) walk down the shore. We pay for the use of lounge chairs and an umbrella on a stretch of beach outside Hotel Atlantico.

Back on the main road (Avenida Aventura), there are clusters of booths selling BBQ’d meats and corn, fried chicken and potato chips, cookies and cocktails. We explore the options around midday finally settling on pulled pork sandwiches. The cart has a whole roasted pig laying across it. The vendor forks off tender meat, piles it onto a roll with salt, pepper and a vinegar based sauce. We are charged 1 CUC per sandwich. Knowing the local customer in front of us paid much less, we haggle for a better rate (3 for 50 CUP), and take a couple more sandwiches for the road. We are being ripped off fairly consistently, charged double and triple what the locals pay, sometimes given incorrect change. It is only a matter of a couple of dollars (a tourism tax, if you will) but a bit frustrating nonetheless.

During the 1940s, Ernest Hemingway made Cuba his winter residence. He rented Finca Vigia, a large property near Havana, for this purpose. His famous fishing boat Pilar – a nickname for his wife, Pauline – was moored nearby. I know I am not supposed to like Hemingway (the self-important, alcoholic, philandering misogynist), but I have a newfound appreciation for The Old Man and the Sea, and can see why he (and boatloads of important artists and thinkers) was so taken with Cuba. During a bender I’m sure, he was quoted declaring, “My mojito in the Bodeguita del Medio and my daiquiri in the Floridita.” So no trip to Cuba is complete without the obligatory Hemingway pub crawl in which we sample both offerings.

El Floridita, located on the corner of Obispo and Avenida Belgica, is packed. We wait it out and manage to grab a table. The tables are serviced by waiters. You can also order drinks directly at the bar. The waiters and bartenders are dressed in uniforms from an era long since passed. At 6 CUC, the daiquiris are expensive, yet delicious. The watering hole also features wonderful rotating bands and a life-sized bronze statue of Ernie perched at the bar for eternity, presiding over the clientele from first pour to last call. It is, without a doubt, a tourist trap but still worth visiting. Also, the restrooms are clean and well-stocked, which is not usually the case.

Next up: mojitos at La Bodeguita Del Medio, on Empedrado just around the corner from the visually-striking Plaza de la Catedral. This haunt is even more crowded than Floridita. We shove our way to the bar to order mojitos (5 CUC each). The talented multi-tasking bartender lines up an entire row of highball glasses. He goes down the line adding sugar and mint, muddling, measuring, pouring, and stirring. The narrow street is crowded with Cubans trying to capitalize on the inundation of vacationing visitors. One woman is selling cigars; another, dressed head to toe in white lace, fans herself while reclining in a wooden rocker on the sidewalk out front a brightly painted building. She sits there, a shrewd businesswoman offering the quintessential Cuban photo-op, but not without a price. She knowingly toys with our frugal photographer, covering her face with the fan each time she spots Syd lurking around the corner. We are approached by a man with long, bushy white mustache, huge cigar between his teeth and crooked black beret. He shows us a tattered copy of National Geographic Poland from 2006 featuring him on the cover. He looks exactly the same, wearing that exact outfit some ten years later. He will happily recreate the image for a small fee. We enjoy dinner and drinks at 304 O’Reilly. The name is conveniently also the address. The tacos, papas bravas and homemade salsa were standouts. After a long sun and rum-soaked day, we take a taxi back to Vedado (negotiated rate of 5 CUC from downtown Old Havana to Vedado).

Chapter Quatro:

Day four finds us traveling to Trinidad, a city centrally located on the Southern coast of Cuba. We arrange transport through our host, Armando (130 CUC total). A well-dressed Cuban picks us up in amazingly well-preserved 1952 Chevy. The pristine white leather seats are covered in clear plastic, like grandma’s furniture. My sweaty legs stick to the plastic as I doze in the backseat during the four and a half hour drive. Have I mentioned the heat and humidity?! Our driver graciously allowed us a quick pitstop in Cienfuegos (a former French colony) on the way. The drive through the lush, tropical landscape is beautiful. The final stretch takes us along the coast with Parque Natural Topes de Collantes to the left and secluded beach coves on the right.

In charming Trinidad, we stay with Jose y Kirenia, the most hospitable of hosts. Their home occupies three different levels, making it the tallest dwelling around so the amazing views are unobstructed and the roof deck secluded. Their home is just outside the city center, a 10-minute walk at most. A walk which we come to relish as we make our way back at the end of each day, recognizing the neighbors, sharing in their sense of community. J y K also host several small dogs, if you are into that sort of thing. For some reason I still cannot explain, I took quite a liking to their miniature chihuahua called Moli, sharing several meals and sunsets together.

That afternoon, we explore the small downtown area and Plaza Mayor. We relax and enjoy coffee at Don Pepe. The glass containing my icy caffeinated concoction was sweating more than I was. We first spotted colorful little espresso cups emblazoned with “Cuba” during a refueling stop on the drive. Spotting them again at Don Pepe, my want for these souvenirs grew. And then, as luck would have it, we happened upon a street stall selling them in every color. The vendor was really sweet and negotiated the price with us since we ended up buying so many. We continue on to the Tres Cruces (Three Crosses) neighborhood. In passing, a little girl asks for something sweet. We don’t have any cookies or treats on us and promise to return tomorrow. “Amigas, que hora?” she asks. Then, we head into La Botija for tapas and garlic shrimp and cold beers.

With most of our needs met and having been “off the grid” since Mexico, we decide to explore the limited internet options. The government-run store that sells internet cards is closed for the day. However, we learn that Iberostar Grand Hotel (across the plaza) sells the cards if you purchase a drink in their bar/lounge area. The internet card is 2 CUC for 30 minutes; cervezas are 3. We oblige, drinking over-priced Cristal and posting our first photos since entering the country. We also responsibly check in with our parents, just so they know we are alive. The service is unreliable, but you are able to sign out and use the remaining minutes another time.

I realize everyone travels differently. We each bring our own agendas and expectations. We require certain creature comforts. Some fastidiously plan; others play it by ear. But if I may step on my soapbox for a second, I would encourage everyone to take advantage of the casa particular accommodations (Havana, Viñales and Trinidad have no shortage of wonderful options), rather than these large government-operated hotels. Sure, it was nice to sip a cold beer and scroll through Instagram in an air-conditioned lobby, but the overall aesthetic is antiseptic and inauthentic. Think Dirty Dancing: Havana Nights before Romola Garai escapes to the streets with Diego Luna.

Where the internet disappoints, the Cuban churros do not. We find a little cart on Rosario Street, just down the block from a graffiti “Cuba” mural. The vendor wears a comically tall chef’s hat. He pipes a long strand of dough into bubbling oil with this industrial-looking crank. He stirs the frying dough around in the oil. When finished cooking, the long strand is cut into small pieces with rusty scissors, collected in a paper cone, and drizzled with condensed milk or chocolate and cinnamon-sugar. Obviously, we made several trips down that street.

Chapter Cinco:

Trinidad is a very small town well-known for its beachy peninsula. Today, we arranged a ride to the beach through our hosts. Rodolfito drives us the 15-20 minutes to Playa Ancon. He has also agreed to pick us up later. The transportation is 20 CUC roundtrip. Rodolfito does not take us all the way to Playa Ancon. Instead, we are dropped at a secluded stretch of beach near Grill Caribe restaurant. The beach is incredible. We pay 7 CUC for a straw palapa and three chaise lounge chairs. The nearby restaurant sells beer and large water bottles for 2 CUC each. The water is unbelievably clear and so refreshing. Eventually, all the umbrellas and chairs are taken, but it is still a perfect, private spot for some rest and relaxation.

After Rodolfito drives us back to town, we ordered personal pizzas from this hole in the wall on Simon Bolivar, just up the street from Circuito Sur. These pizzas, advertised as “pizza calientes,” were the best we had in Cuba and cost only 6 CUP! The spongy dough was topped with sauce, ham, cheese and onions, assembled in a small cast-iron tin, and cooked in a large BBQ smoker. We took them to-go and ate on our private roof deck.

As promised the day before, we head back to Tres Cruces with some cookies and stickers and notepads brought with us for the sole purpose of sharing with Cuban children. Our “humanitarian” mission starts off well enough, but quickly we are mobbed by children, their small outstretched hands reaching for things we were unable to give. In a futile attempt to foster unity and goodwill, we unwittingly became this apropos microcosm of U.S. foreign relations leaving chaos and division and inequity in our wake. The encounter left us ashamed and distressed that, despite our best intentions, we may have done more harm than good.

While researching accommodations in advance, we noticed prior guests praised the food at Jose and Kirenia’s. In the morning, we had requested dinner at their place. Jose does his shopping during the day, so we could enjoy a delicious dinner that night. We had soup and salad, rice, beans, yucca and lobster tails. There were some little cakes for dessert. Each meal was 12 CUC. They sold drinks separately or you could bring your own. On that roof terrace, the meal went down as exquisitely as the sun.

There are several bars and live music venues in Trinidad, but the biggest draw by far is Casa de la Musica. Many patrons sit on steps and curbs around the main plaza and listen from afar. For 1 CUC cover charge, you can get a better look. We are ushered to unclaimed seats on the ascending cobblestone steps that create the makeshift outdoor amphitheater. Full-service waiters consistently come around taking drink orders (2-3 CUC), the bands rotate every hour or so, and enthusiastic amateurs and trained professionals take to the floor to dance the salsa. It is a perfect spot to enjoy the local musical stylings alfresco and people watch or partake depending on your preference.

Chapter Seis:

There is not much to do in Trinidad proper. There are day trip tours of sugar plantations and other sights in the area. There are also several hiking options in nearby Parque Natural Topes de Collantes. I researched some trails to waterfalls and swimming holes, but we are concerned about the heat and do not want to spend a lot of money. Rides and guides can really add up. Instead, we plan another beach day. This time we rent bicycles. I use the term rent loosely because essentially we are paying (5 CUC each) to borrow the bikes of three townspeople. Cuba is not equipped for this influx of tourists and resources are scarce. They do not have bike rentals on every corner. Yet. But, in the meantime, they will do everything in their power to accommodate you. A nice young man brings the bikes to our casa. He adjusts the seats, pumps air into the tires, shows us how to use the lock, and off we go.

Slowly and unsurely, we retrace yesterday’s route. We ride all the way to Playa Ancon (about 7 miles), since yesterday we stopped short. The beach is expansive and crowded. There are resort hotels and tour buses loaded with beachgoers. Having seen enough, we backtrack to yesterday’s beach. We stake out a similar area. We cannot take the bikes on the beach, so we have to pay an old woman 1 CUC to keep an eye on them. Our bikes were safe and sound. I, however, did not fare as well. During a dip in the ocean, I managed to step directly on a sea urchin. I instinctively pulled my foot away, but several spines broke off in the bottom of my foot. I continued soaking it in salty ocean water and attempted, without much luck, to extract the spines. As the pain subsided a huge storm rolled in, bringing with it thunder, lightning and a plague of dragonflies. There must have been hundreds of insects swarming the beach, either displaced by or escaping the torrential rains. Once the storm cleared, we made like the dragonflies, and rode our bikes back as quickly as possible.

Our favorite pizza place, which we had our hearts set on, is closed this afternoon. Aye, Cuba! Luckily, on the corner of Rosario and Gutierrez, we find delicious pulled pork sandwiches for 1 CUC. After a difficult ride and my brush with death, we inhale two each.

Then, we find the best churros yet at a stall around the corner. We return to Iberostar Hotel to use the internet again. Apparently, sea urchin spines are mildly poisonous, the confirmation of which does little to assuage my alarm. The internet states that the spines will dissolve in vinegar, which, in Cuba, we don’t have. The main risk factor is infection, so I try to keep the area clean (easier said than done in sandals on dirt roads), and check the likes on my prior post.

Later that day, we find this cool bar called La Canchanchara. Other than the live music and secluded patio, the main attraction is its eponymous cocktail made with rum, honey, lemon and seltzer. They are 3 CUC and delicious! Also, the bartenders are very good-looking. We enjoy our drinks, the musical stylings and a cigarillo purchased earlier at the hotel. We wander around to a few other bars, listen to more live music. On the way home, we order a couple pizzas from a very busy cafeteria. It is the only open establishment in the area. The long line is comprised of twenty-somethings grabbing frozen pizzas and juice, an elderly woman having ice cream scooped into her own mug, and a young man filling tupperware with baked goods. Now, of course, we need dessert. On Rosario, we find El Rico’s churro cart, which is also very crowded. El Rico is surrounded by a gang of young boys. They all live in the neighboring houses and hang around the cart eating churros each night. A couple of them chatted up Kate (our sole Spanish speaker) and one of them went so far as to offer her a piece from his churro cone.

At night, the Trinitarios either sit on their stoops and gossip or attempt to cool off inside watching television next to electric fans. The adults are more reserved, perhaps a little amused, but mostly unfazed by our presence in their streets and at their cafeterias. It is the children who are uninhibited and bold (and so photogenic): a girl with thick glasses asking for a pen; another sitting on one of the crosses in Tres Cruces, her hand patiently raised for sidewalk chalk; boys taking a rest from soccer, splitting Nutter Butter cookies in half, posing for our photos; one little boy “playing” a trumpet; an even younger boy – still in diapers – spooning Nestle chocolate ice cream straight out of the pint container; the baby girl accompanying her grandpa on a late-night cafeteria run, smiling through her pacifier, waving adios.

Chapter Siete:

Today we are driving, or rather being driven, to Viñales. We enjoy breakfast at our casa particular (5 CUC each). Jose and Kirenia also helped arrange transport to Viñales for 40 CUC each. The three of us are shuttled to a meetup point just outside Havana where we meet up with a group of eight also heading to Viñales. We drive through a crazy afternoon storm. Rain pours through the open back windows; the driver can barely see the road ahead. Soon, we begin our descent. The road steeply winds into the valley. We can see bold bicyclists gaining on us in the rear view. We pass a hotel on the hill overlooking the valley. The restaurant, patio and pool boast unrivaled views. Once in Viñales, we pick up this affable local, who apparently knows all the casas in the area. He directs our driver to each drop off location.

We are staying at Villa el Habano (30 per person per night). As is our preference, it is a short walk from the downtown area. Each room features a well-stocked minibar and front porch enhanced with solid wooden rocking chairs. Our host, Yanika, is really nice and helpful. We settle in and make arrangements to have dinner prepared that night.

There are scattered showers throughout the day, but we decide to explore the city in spite of the inclement weather. The main street is lined with restaurants and bars. Only 90 minutes from Havana, Viñales is definitely a party destination with most visitors just coming for a day or two. Viñales is also an Unesco World Heritage Siteprimarily known as the lush valley where the country’s smoking tobacco is grown.

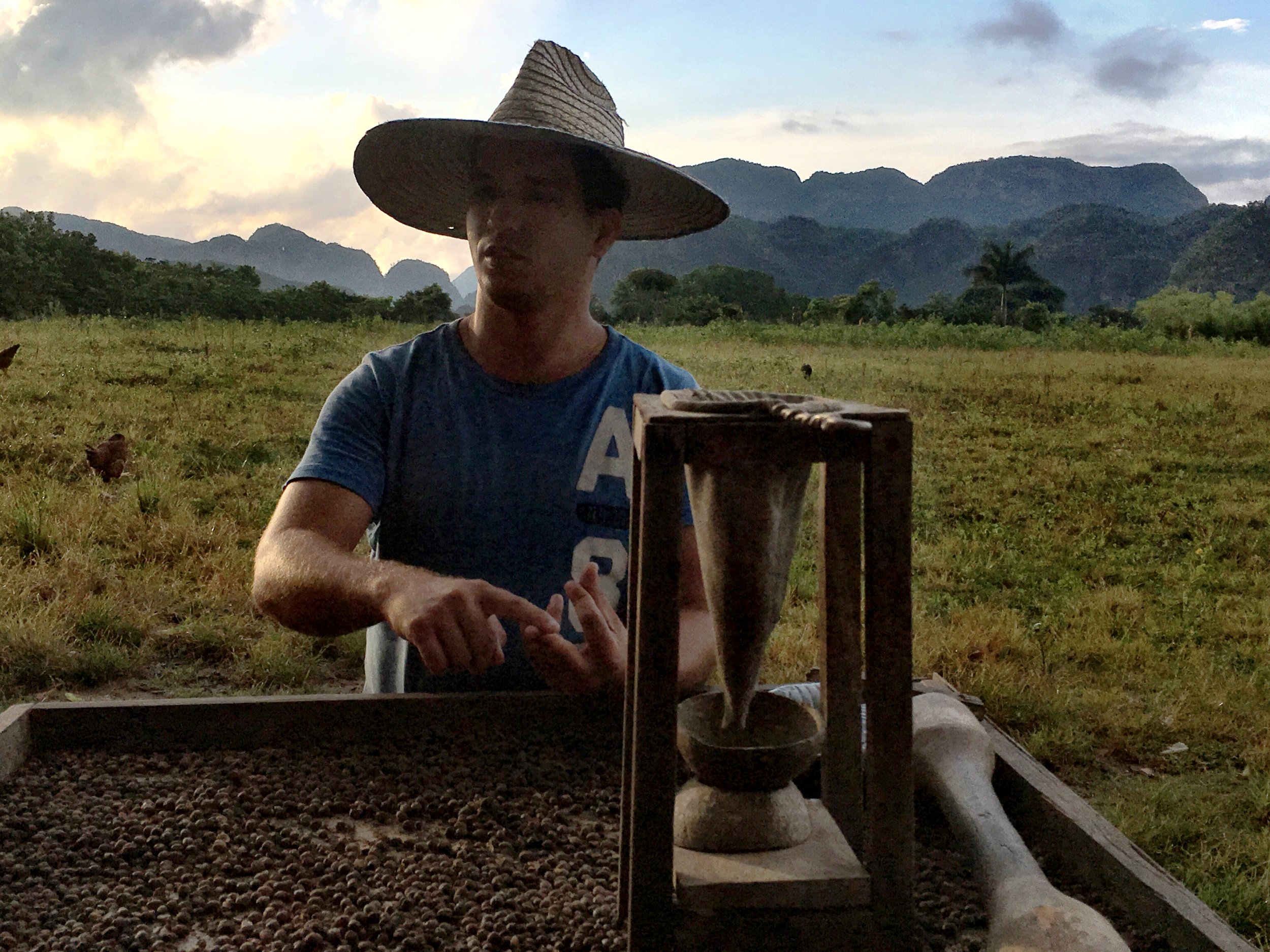

On our travels, we meet one such tobacco farmer, Domingo, who is out walking with his dog and grandson, David. He showed us his humble farm where he lives with his wife, mother-in-law, three daughters, son-in-law and David. His son-in-law is training horses in an arena out front. His wife offers us coffee. Domingo offers us seats at a table in the backyard where goats and chickens graze. He thoroughly explained the tobacco process from planting and harvesting to drying and rolling, all while transforming his own crop into a cigar before our eyes. Taking dried tobacco leaves, he separated the blade from the nicotine-concentrated stem and hand-rolled cigars for us (2 CUC each). He told us that farmers are only allowed to keep/sell 10% of their annual crop; the other 90% is sold to the government at price it determines based on quality, color, etc. These tobacco leaves are then processed at government-operated facilities with high name recognition, i.e. Cohiba and Romeo y Julieta. So, in theory, those coveted Cubans are comparable to the cigars we bought off Domingo for a fraction of the price. Meanwhile, the government lines their pockets selling overpriced cigars, while Domingo and his family live in a two-bedroom farmhouse. From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs, right?

According to our needs, it is dinner time. Yanika and her mother prepare a delicious dinner of soup, rice and beans, and choice of meat. Both the pork (10 CUC) and shrimp (12) were delicious. There is fruit and flan for dessert.

Chapter Ocho:

This morning, Yanika helps arrange a walking tour of the mountain community of Los Aquaticos. A kilometer beyond the turn-off to Dos Hermanas and the Mural de la Prehistoria, a dirt road twists up the mountain. Los Aquáticos was founded in 1943 by followers of a visionary who discovered the healing power of water when the farmers of this area had no access to conventional medicine. They colonized the mountain slopes and two families still live there. Los Aquáticos is accessible only by horse or on foot.

As we embark, our guide points outs a blue house halfway up the mountain. This is one of two remaining residences in the community. From there, you can admire the view, procure grown-on-site coffee and chat to the amiable owners about the water cure. We pass the blue house without stopping. Our guide veers right instead, leading us to a small hut with unmatched views, overpriced mojitos (and perhaps a friend providing a kickback!). The farmer who lives there grows his own mint, uses honey instead of granulated sugar, clears out the single room for salsa lessons, and even installed his own solar panels that cleanly power the whole operation. The three-hour walking tour cost 4 CUC per person per hour plus 5 CUC taxi ride each way. Our tour guide, Andy, spoke English well. Although, he recounted more inappropriate and unfunny jokes than historical information. Then, while posing for a photo at the viewpoint, he was kicked in the ribs by a grazing horse. He iced his injuries with a cold soda and led us down the mountain in a more subdued manner. After your visit, you can make a loop by returning via Campismo Dos Hermanas and the Mural de la Prehistoria cliff paintings. The complete Los Aquáticos–Dos Hermanas circuit totals 6km from the main highway. Supposedly, it is a wonderfully scenic route, albeit less traveled. But one we do not go down, the company of Andy and his antics having made all the difference.

We asked Andy for lunch recommendations. At his suggestion, we had the taxi driver drop off us at small cafeteria, Rompiendo Rutina. We ordered pretty good pizzas for 2 CUC. There was a small store across the street that sold jugs of water and trays of vanilla sandwiches cookies. We stocked up on both. I would recommend buying bottled water (also cookies!) whenever you have the chance because stores tend to run out later in the day. After lunch, we walked to the home office of Yoan and Yarelis Reyes – the premiere tour guide outfit in Viñales. Yarelis helped us arrange a sunset walking tour of Valle del Silencio for that evening.

In the afternoon before the tour, we return to Domingo’s house. We wanted to bring him and his family some cookies and sidewalk chalk. We ended up getting caught in a really intense lightning and thunder storm. Domingo and his family were gracious enough to provide shelter and coffee. We chatted with his daughters and grandchildren for a bit. His poor wife and mother-in-law were so terrified. The bright flashes and roaring thunder move them to tears. I was frightened, too, but figured these types of storms were commonplace. Seeing them, embracing and crying, did nothing to assuage my fears. We said our goodbyes and scrambled back along the slick muddy path. Each tremendous flash of lightning was immediately followed by cracking thunder and our piercing screams. Between the approaching lightning and tenuous electrical lines, I really thought we might die. We were out of the woods, literally, but the storm raged on. Back on the street, we were offered shelter at another home. Juanito – no shoes, no shirt, no problem – was out front squeegeeing water off his porch. We hunkered down under his awning as he regaled us with tales of earthquakes and hurricanes; quizzed us on the great men of the Americas; and took our political temperature. Obviously, we’re with her. He offered to take us on a tour of the surrounding valley tomorrow for 5 CUC each. His sales pitch even included a hand drawn map and stack of photographs sent to him by happy customers. We never did take him up on his offer.

The storm cleared just as quickly as it appeared, and we rushed off to our next walking tour through Valle del Silencio. Silent in name only, the valley is abuzz with birds chirping and insects humming. Our feet splash and suction as we slosh through muddy paths. Sounds hang in the air, which is thick from the day’s rain. Our guide, Emiliano, was really funny and knowledgeable. He took us through the beautiful valley describing the various flora and fauna. We made obligatory stops at a coffee plantation (where fresh sugar cane and coconut juices were sold) and a tobacco farm (where cigars were freshly hand-rolled and sealed with honey). We caught the final minutes of an extraordinary sunset while smoking a complimentary cigar, basking in the sheer wonder and tranquility of the valley below. We told Emiliano about our earlier tour and he even knew infamous Andy. He and the cab driver started to laugh, sharing in a private inside joke. I guess the Viñales guide community is a small one.

After narrowly evading lightning strikes and completing our second walking tour of the day, we chose not to the break the routine and returned to Rompiendo Rutina for dinner. This time, we ordered their specialty plates with fried chicken and ropa vieja (pulled pork with red sauce) served with rice and black beans and plantain chips (3.50 CUC each). You will see ropa vieja on food menus throughout the county. Its name translates to “old clothes” and the story goes that a penniless old man once shredded and cooked his own clothes because he could not afford food for his family. He prayed over the bubbling concoction and a miracle occurred, turning his old clothes into a tasty meat stew.

The influence of the Spanish colonialism remains evident in the country’s historic architecture. In each city we visited, the focal point of the main central plaza is a church. There are elaborate cathedrals with functioning bell towers and looming crucifixes – some well-preserved; others in decay – erected as places of worship for Spanish Catholics that now stand in direct conflict with Communism’s ambivalence towards religion. Some have been converted into museums; others stand as symbolically abandoned vestiges of a faith forsaken. The opium of the people is a hard habit to kick. Speaking of kicking habits, we were really jonesing for some churros, but unable to procure any while in Viñales.

Chapter Nueve:

We begin the day with a large breakfast at our casa (5 CUC). Yanika’s mother made the most amazing flan. We requested seconds. And thirds.

In the Viñales valley, tourists are not supposed to explore without the aid of a guide. We found this to be more of a suggestion than enforced rule. Because of the heat and unmarked, circuitous trails, it is advisable to have a knowledgeable guide with you. On a country road, just outside town, we bump into a farmer. He tells us a bit about the surrounding area, how this road will lead to hiking trails in the direction of caves carved out of the imposing limestone karsts and natural swimming holes. We listen closely to his directions, throw caution to common practice, and decide to try to find this elusive swimming hole on our own. We encounter lots of people along the way, mostly guided horseback tours. We ask each and every one for directions, receiving a different response/estimate each time. We even cross paths with the couple staying in the room next-door at Villa el Habano. At a barn, we encounter another tourist, traveling alone with her Cuban guide, who leads us the rest of the way to the swimming hole. Horses parked at the top of the stairs indicate we are in the right place. There is a small changing room, bar and restaurant. The murky pool, which could provide a home to any number of waterborne creatures, may be the stuff of nightmares to some. But, to us, after hiking for two hours in baking heat, it was an oasis.

We part ways with the other swimmers and attempt to head back the way we came. The trails are very muddy after yesterday’s storm. Conditions are made worse by all the hooves that came before us. We rely on makeshift hiking sticks to steady ourselves, but not without a few pratfalls. Near the end of our hike, we strike up a conversation with a twenty-something Cuban, David. He is out exploring, trying to learn the trails in order to become a successful guide in the area. Formerly an English teacher with a monthly salary of 24 CUC, he left his chosen vocation to pursue this new career. With the influx of American tourists, English is a valuable marketable skill. He can make exponentially more money as a tour guide than he ever would teaching public school. This is a familiar story, one also shared by our guide yesterday. It gives me cause for concern with respect to the state of education in Cuba as well as the inevitable expansion of inequality between private- and public-sector employees.

Chapter Dies:

Today, we are heading back to Havana, where we will spend our last night in Cuba. We get pizzas at Rompiendo Rutina (of course!) for lunch and stock up on bottled water and ice cream for the bus ride. The day before, we purchased bus tickets (12 CUC each) at the Viazul office in town. Our 2:30 p.m. departure was completely full so if you opt for the bus, rather than a shared taxi, it is advisable to purchase tickets early. The ride was scheduled to take just under four hours with a brief stop at Las Terrazas. In reality, it broke down constantly and took over five. I was happy to get a glimpse of Las Terrazas. The pioneering ecovillage was centered around a large reservoir and swimming hole. It is a great destination for backpackers with a variety of hiking and birdwatching options, in addition to the more upscale Hotel Moka.

In Havana, we are staying at another casa in Vedado. It is pouring rain so we took a taxi from the bus station to our accommodations. Yanila has a huge house with swimming pool, restaurant and roof terrace. All the rooms were booked, but she had a small apartment across the street available (30 CUC per night). The Viñales weather followed us to Havana so we dined at a nearby cafeteria. Pizza was the most reliably palatable meal. A lot of the meat and fresh fruits/vegetables are suspect. We chatted with a man while he was waiting for a takeaway order for his family. He had some relatives that were able to get refugee status and emigrate to the U.S. Some people got out years ago, but most Cubans we spoke with have not traveled at all, even within the country.

Chapter Unce:

We had breakfast at our casa. A decadent spread with fresh juices, sliced ham and cheese, fruit and baked goods. We wanted to make another pass by Coppelia, but it is closed on Mondays. As is the highly recommended cafe Cuba Libro. So we head to the beach. Yanilla helps us arrange a ride to Playa Santa Maria that morning, then a ride from the beach to the airport. Ernesto will take us both ways, so we are able to leave our luggage in the car. He drops us off near Hotel Atlantico again. We claim a similar area as our first visit. It being an overcast day during the week, we are a little worried about finding open restaurants or retailers in the area. Fortunately, the tamale and pork sandwich stands were open for business and a food crisis was averted. We glutinously bought two tamales, ten (!) pulled pork sandwiches, piña coladas, and wafer cookies for the road. Our farewell meal.

Ernesto then drove us to the airport. His little car sustained a broken windshield wiper and flat tire during the course of the ride. He is, of course, handily able to fix both. We leave him with a couple of fashion magazines and tubes of Chapstick for his wife and our sincerest thanks.

A couple hours later, we are off, en route back to Mexico City for the night. We have some issues with our pre-arranged airport pick up. But after purchasing a calling card and phoning our host we are successfully picked up and taken to our Airbnb. This particular place was chosen solely for its proximity to the airport. We have a flight back to Los Angeles first thing tomorrow morning.

Chapter Doce:

Using Mexico City as a gateway to Cuba also provided the perfect excuse to check out this awesome capital for a couple days. We stayed two nights at an Airbnb in the hip and artsy Roma District. Our accommodating host picked us up a the airport when we first arrived. Redeyed after the overnight flight from Los Angeles, and in desperate need of a nap, he let us snooze on bunks in the unoccupied dorm-style room as our private room was not made up yet.

Feeling refreshed, we take on the city. But first, coffee at Cafe Milo. As for provisions, there are pop-up taco stands on every corner and we sample several. Unsure of the offerings, but never one to shy away from unidentifiable street meat, we point to different piles on the grill. The vendor serves up the tacos on reusable plastic plates. He has buckets of juicy limes and homemade salsa (so spicy!) and a cooler of drinks. We join the locals in quickly consuming the tacos sidewalk-side before continuing our stroll. Bosque de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Forest) is this huge park with a castle and zoo near La Condesa. Snack and souvenir stalls line the gravel walkways. Pedal and row boats skim across the lake. We find arguably the greatest souvenirs ever made: cheap slip on shoes adorned with various portraits of Frida Kahlo. We fail miserably at negotiating the price down (the vendors could tell how badly we wanted the shoes) and successfully walked away with five pairs between us.

We explored the historic downtown area and Zócalo plaza. We endeavored to view Diego Rivera’s mural located at Secretaría de Educación Pública, but could never get the opening hours quite right. Since this is a government office admittance is free so long as you leave your photo ID with the guards. Our appetites not diminished by the disappointment, we sample more street food. This time we try the chicken flautas topped with salsa verde and cheese. Everything we ate was amazingly delicious. Despite (or perhaps because of) our cavalier attitudes towards dining al fresco, we never got sick from questionable food safety or microbes in the air. If you are nervous, I would recommend starting slow. But keep in mind that all food is prepared with bottled water. The Mexicans do not drink the tap water either.

Desperate for some Rivera murals, we visited Museo Mural Diego Rivera next. This small museum was built in 1988 to house one of Rivera’s most famous murals, “Dream of a Sunday afternoon in Alameda Central Park.” The 50-foot fresco was originally painted in 1947 for the dining room of the Hotel del Prado. The architect proposed the theme Alameda Central due to the hotel’s close proximity to Mexico City’s first city park, which was built on the grounds of an ancient Aztec marketplace. In 1985, the hotel was nearly destroyed by an earthquake. The restaurant that initially housed the Rivera mural was completely in ruins, but the mural, now in the lobby, could be rescued and painstakingly moved to its current location. Fittingly, the museum and its mural now neighbor its namesake, Alameda Central Park.

Entrance to the museum is 30 pesos. If you want to take photographs of the works in the museum, you must pay an extra fee. The museum provides a chart that helps you understand who each of the multitude of figures in the painting represent. We were making our way through the figures when a kind elderly gentleman took it upon himself to explain the concept of the mural. Not unlike Rivera, he took us through the entire mural. In chronological order, starting from left to right, we meet numerous prominent figures from Mexican history joined together in a stroll through the park. The left side of the composition highlights the conquest and colonization of Mexico; the fight for independence and the revolution occupy the majority of the central space; and modern achievements fill the right. In the center of the mural is Diego Rivera at the age of ten being led by the hand by a skeleton woman created by the popular Mexican engraver Jose Guadalupe Posada. Posada was a big influence on Rivera’s work. His likeness is also featured in the mural’s central quartet. And Frida Kahlo makes four. In its surreal way, the mural juxtaposes the sometimes grotesque and nightmarish reality of both historical and fictionalized figures with their internalized dream worlds. The mural’s overwhelming beauty and scale and this man’s astute insight made for a dream of a Wednesday afternoon for these weary travelers.

Through Viator, we booked a tour of Xochimilco, Coyoacan and Museo Casa Azul. We are picked up at our Airbnb and shuttled to the main meeting point outside a hotel in downtown Mexico City. The ride to Xochimilco is about 30 minutes. Xochimilco – translated from the Aztec’s Nahuatl language as “garden of flowers” or “place where flowers grow” – is an outlying borough of Mexico City. One of the most cherished Sunday traditions is spending an afternoon floating through the canals on brightly painted, covered wooden pole boats called trajineras, having a long lunch and enjoying mariachis playing on passing barges. As is customary, the trajineras are named after women. Lolita and Lizbeth and Ana Luisa are stacked in the dock area like tetris pieces. Onboard, we are seated in chairs arranged around a long table running down the middle. We are accompanied by an English-speaking guide. Our boat is guided down the river by a Mexican gondolier. As we make our way through the canals past greenhouses and nurseries, other boats pull up alongside ours to sell tacos and roasted corn (elotes and esquites), beer and sodas, flower crowns and sombreros. At one point, an entire mariachi band and their instruments comes aboard. Each song costs 100 pesos and they keep playing until the passengers stop shouting out requests. Their little boat follows in our wake. When they have finished playing, they get back in their boat, and we are forced to split the bill. The whole thing is a tourist trap, but otherworldly enough to make it worthwhile.

We say farewell to the buoyant broads of Xochimilco and devote the rest of our afternoon to another formidable woman, Frida Kahlo. Before our tour of Casa Azul, Frida’s home-cum-studio turned museum, we are free to explore the neighborhood of Coyoacan. We abstained from eating on the boat, saving ourselves for tacos and churros in Coyoacan. We also indulge in seafood tostadas from the Tostadas de Coyoacan stall in the local marketplace.

Frida’s story is amazing. She lived in this one neighborhood most of her life. Casa Azul, named for its cobalt blue walls, was her childhood home. Frida survived two near-fatal incidents while living there. A childhood affliction with polio left one leg shorter than the other. Later, at the age of 18, she was badly mangled when the bus she was riding collided with a trolley car. During the crash, an iron handrail went diagonally through her pelvis, fracturing the bone. She also displaced three vertebrae confining her to bed rest and requiring she wear a plaster corset. She somehow survived the horrific accident, but would endure the physical and psychological effects of the accident for the rest of her life. The confinement of her recovery afforded her the opportunity to throw herself into her work. She was able to paint self portraits from bed with a specially designed easel and mirror hanging above her.

The pain and shame of never being able to bear children (a consequence of the trolley accident) manifested in her emotionally raw sometimes fanciful work. Many of Kahlo’s self-portraits mimic the classic bust-length portraits that were fashionable during the colonial era, but also subverted the format by depicting their subject as less attractive than in reality. She was all too familiar with the horrors life can inflict. She also often featured her own body in her paintings, presenting it in varying states and disguises: as wounded, as a child, broken or costumed. Her paintings often depicted the female body in a very unconventional manner, such as during miscarriages and childbirth or cross-dressing. In her professional life, she used her art to push the boundaries of female norms and societal expectations. She defied convention in her personal life, too, marrying Diego Rivera, the famous muralist and infamous womanizer. They eventually divorced, and then remarried the next year, remaining a couple until her death. Near the end of her life, she and Diego moved back to Casa Azul, where she eventually died in 1954.

The museum is littered with their personal effects, artifacts of lives they led together as lovers and separate as artists. A house left in organized disarray. In her studio, her wheelchair sits facing her easel, a half painted canvas leaning against the frame. Still life interspersed with art. The house occupies three levels: vibrant outdoor garden; kitchen, living area, Diego’s room; Frida’s studio and bedroom. It must have been nearly impossible for her to navigate those stairs as her condition worsened. Being in that space, with her belongings, you could feel her inspiration and her affliction.

Tickets cost $130 pesos during the week. Make sure you pay the extra $20-60 pesos to take photos inside the museum. Entrance fees are cash only and the museum gets quite crowded. We were able to avoid the long line since our guide purchased the tickets (included in the Viator tour) while we ate and explored Coyoacan. We were left to explore the museum on our own, unaccompanied by the guide.

The tour is scheduled to take us back to our accommodations, but it took longer than expected and we are pushed for time, so plan on taking the metro to our dinner reservations. The subway system is really easy to navigate. However, this time, each station we came to had run out of single ride tickets. We walked to at least three subway stations on different lines before we found one with tickets for sale.

After seeing the announcement that Quintonil was named one of the world’s 50 best restaurants in 2016, I promptly made a reservation. We dined a la carte rather than the full eight course tasting menu. We ordered charred avocado tartar, salbute with cuitlacoche and chilli powder, shrimp flautas with squash blossom, creamy green rice with a perfect egg, and their signature mezcal cocktail. Dessert was a deconstructed panna cotta topped with sweetened corn crumble, mamey seed ice cream and edible flowers. The vibe is relaxed yet elegant. Chef Jorge Vallejo, a protégée of Pujol’s Enrique Olvera, and his wife, Alejandra Flores, run the back and front of house, respectively. She even shared the wifi password with us. Everything was incredible. I am eager to return to both the restaurant and Mexico City.

Epilogue:

Early on, we lied about being American, worried the Cuban people would treat us differently (read: unfavorably) if they knew. We quickly came to learn that they could not care less about our nationality. They were excited to have us there, to share stories of Cuba’s history, to discuss American politics. They understood something which I have failed to comprehend time and again: any and all disagreements begin and end with our respective governments. For us, in that singular moment or conversation or interaction, we were simply people living our lives. Most of the Cubans we met had never traveled from the cities or towns where they were born. They lacked the means to explore their own country, let alone leave the island. They are just trying to get by, to survive. They do not have the luxury of immersing themselves in another culture. They do not have time to worry about foreign policy missteps. For them, showing us around, sharing their own stories, introducing us to their families, imparting some knowledge about their life and country and culture gave them agency and us an important understanding of the lens through which they view themselves and the world.